17th May. 1959.

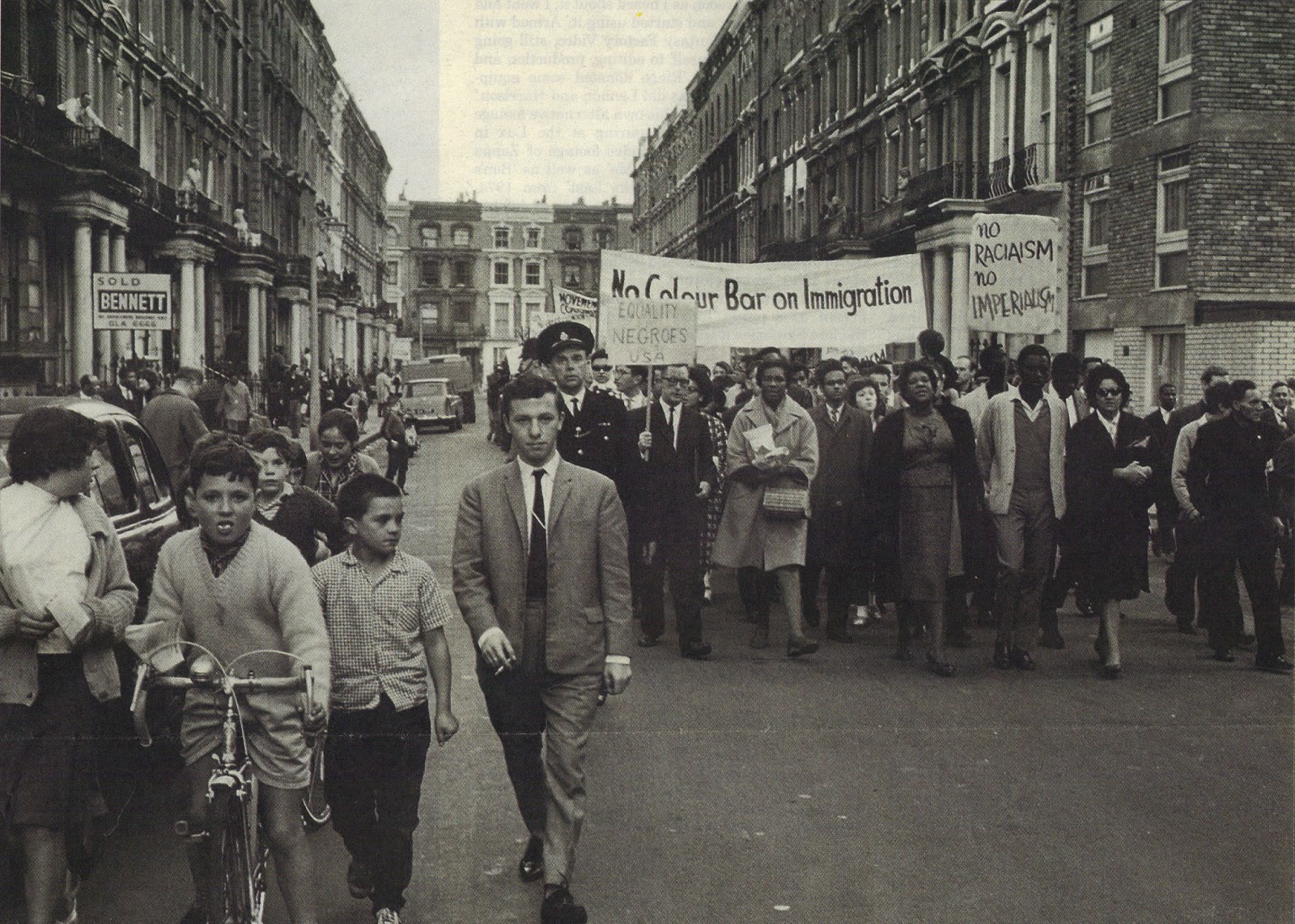

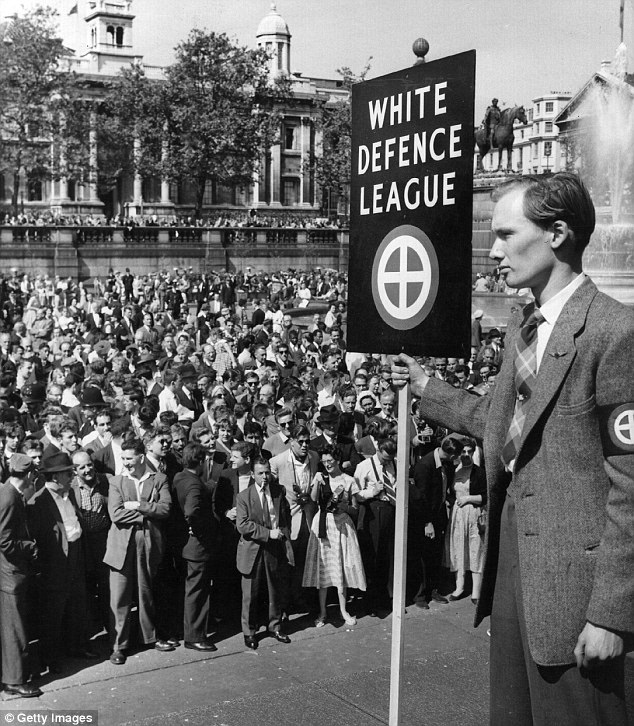

It had been a few months since riots had swept UK cities during the end of the previous Summer. Riots that were the result of relentless attacks on black and brown people. Attacks that had been going on for many years and were understood to be a part of life in the United Kingdom.

But, this time perhaps it was different.

But, this time perhaps it was different.

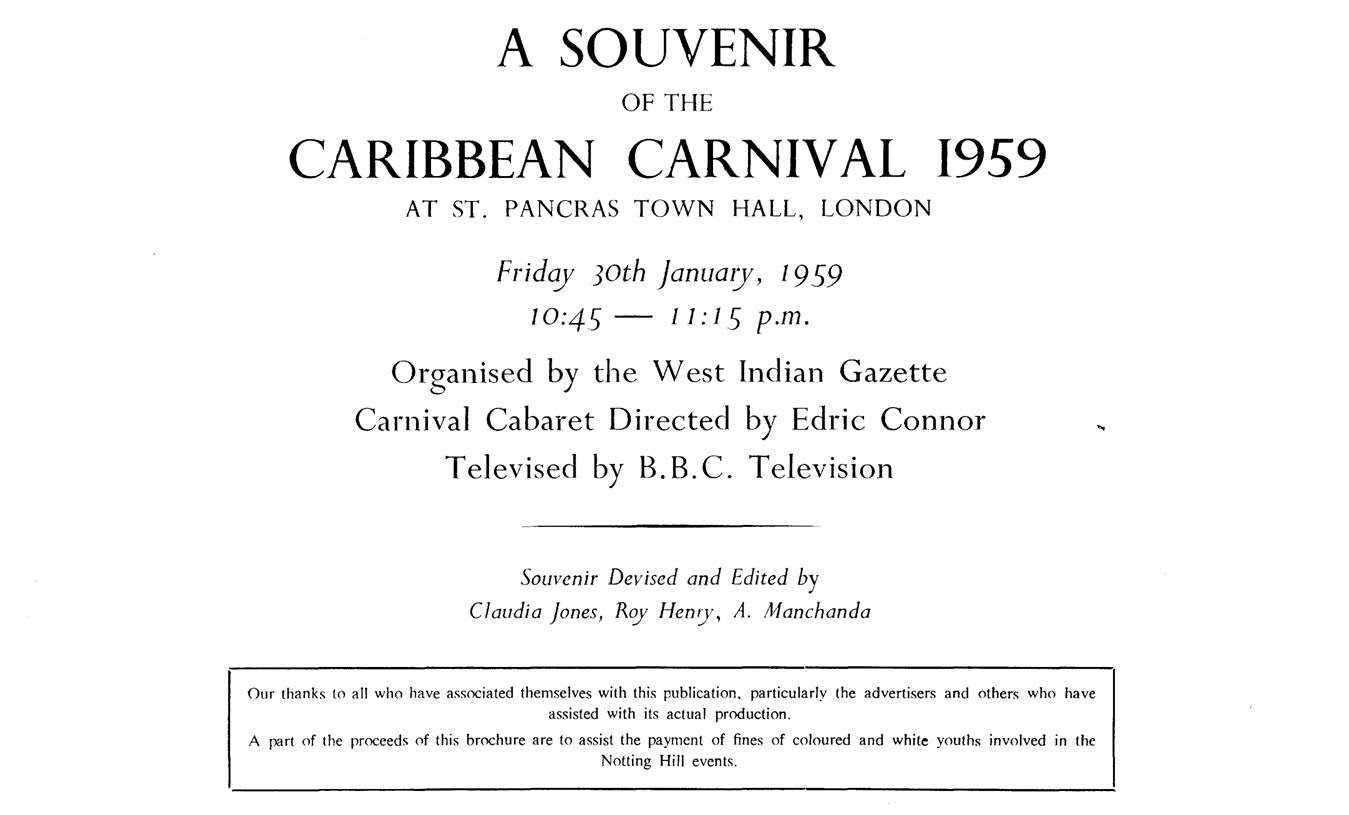

Claudia Jones' first indoor Carnival took place in a West London hall a few months after the riots, as a way to "wash the taste of Notting Hill and Nottingham out of our mouths".

Black people were in the eye of a storm and it had some way to go.

It is always tempting to see only what is in front of us. It can separate our own situation from those of others beyond our immediate reach. But, history tells us that conflicts, revolutions and movements of any kind are instigated by and made up of waves that reverberate through borders and across oceans and make connections that remain.

We are connected in the immediate by our senses.

And across time and space we are connected by stories, disseminated through spoken and written word and imagery and the arts in countless shapes and forms that touch our senses and raise our bodies into action.

People are inspired by other people.

Black people were in the eye of a storm and it had some way to go.

It is always tempting to see only what is in front of us. It can separate our own situation from those of others beyond our immediate reach. But, history tells us that conflicts, revolutions and movements of any kind are instigated by and made up of waves that reverberate through borders and across oceans and make connections that remain.

We are connected in the immediate by our senses.

And across time and space we are connected by stories, disseminated through spoken and written word and imagery and the arts in countless shapes and forms that touch our senses and raise our bodies into action.

People are inspired by other people.

"A People’s Art is the Genesis of Their Freedom"

The central commemorative plaque for Kelso Cochrane, made in 2008/9 with local children and elders.

The surrounding artwork is the 60-metre street-long mural produced in 2008 with over 100 local children.

In 1957, black students of Black Rock High School were breaking down Jim Crow segregation in the United States with the help of state troops.

That same year, Martin Luther King visited Ghana and Nigeria.

Between 1956 and 1960, over twenty African states gained their independence. More followed.

In 1958, 'Stride Toward Freedom', Martin Luther King's account of the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, was published.

The Bristol Bus boycott came about in 1963, the same year that Malcolm X referred to the racial issue of segregation and resulting demonstration in particular as a powder keg ("Any time you put too many sparks around a powder keg, the thing is going to explode, and if the things that explodes is still inside the house, then the house will be destroyed").

Pressure was building and authorities across the globe were being forced to respond.

That same year, Martin Luther King visited Ghana and Nigeria.

Between 1956 and 1960, over twenty African states gained their independence. More followed.

In 1958, 'Stride Toward Freedom', Martin Luther King's account of the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, was published.

The Bristol Bus boycott came about in 1963, the same year that Malcolm X referred to the racial issue of segregation and resulting demonstration in particular as a powder keg ("Any time you put too many sparks around a powder keg, the thing is going to explode, and if the things that explodes is still inside the house, then the house will be destroyed").

Pressure was building and authorities across the globe were being forced to respond.

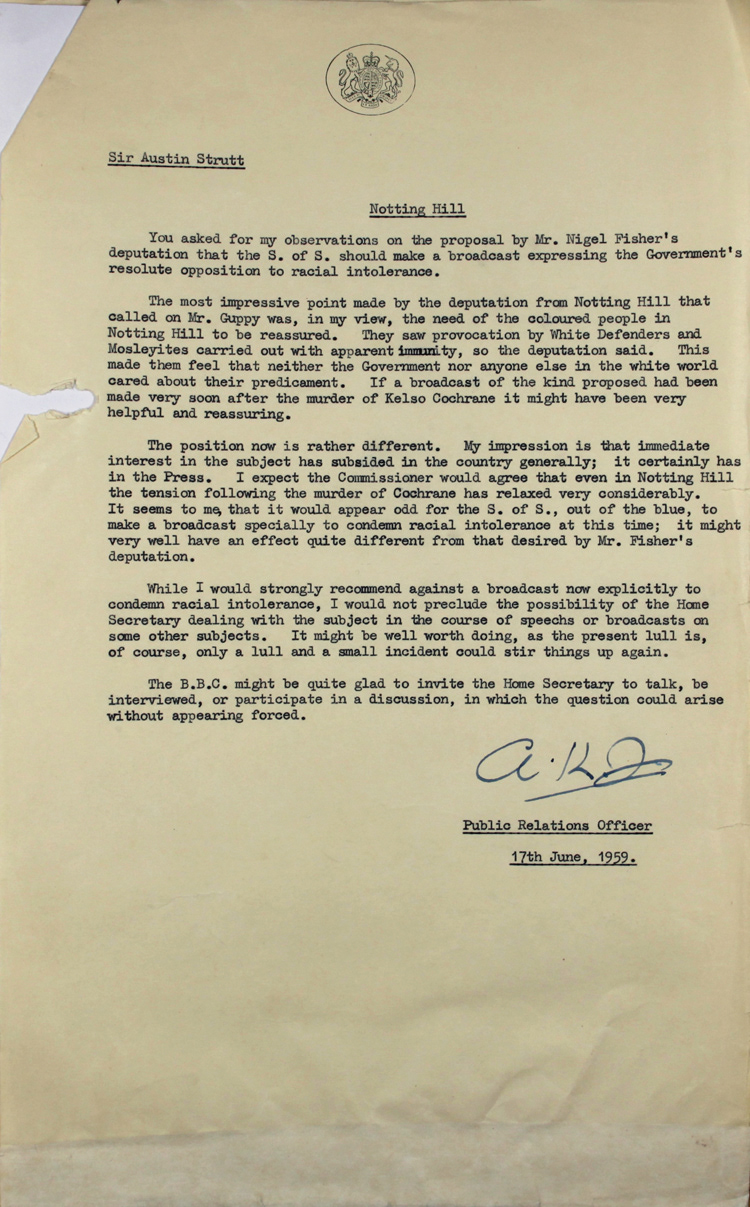

The UK has a particular way of responding to any issue, led by its imperialist classes.

We are stuck with an idea that certain people are born into power and governance, regardless of ineptitude. It is an idea that evidently kills people but, refuses to die. There is no questioning it and so the only challenge for the powerful is one of maintaining quiet and dignified control, even in moments of complete and catastrophic failure.

George Orwell captured many details of the culture in his 1941 essay, 'The Lion and the Unicorn' and it is shocking how many of his observations still hit the mark.

Change does come. But, it is too often painfully slow and, like so much British food without immigration, it often arrives watery, bland and either under or over cooked.

The UK's Race Relations Act in 1965 - the first British legislation to address racial discrimination - was a classic example. A weak British government response to what had been an immense decade of activity for black people in the UK and across the world. It required amendments in 1968 and 1976 and was eventually repealed by the Equalities Act of 2010. The 1965 Act followed the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act that slowed the flow of African Caribbean immigration.

We are stuck with an idea that certain people are born into power and governance, regardless of ineptitude. It is an idea that evidently kills people but, refuses to die. There is no questioning it and so the only challenge for the powerful is one of maintaining quiet and dignified control, even in moments of complete and catastrophic failure.

George Orwell captured many details of the culture in his 1941 essay, 'The Lion and the Unicorn' and it is shocking how many of his observations still hit the mark.

Change does come. But, it is too often painfully slow and, like so much British food without immigration, it often arrives watery, bland and either under or over cooked.

The UK's Race Relations Act in 1965 - the first British legislation to address racial discrimination - was a classic example. A weak British government response to what had been an immense decade of activity for black people in the UK and across the world. It required amendments in 1968 and 1976 and was eventually repealed by the Equalities Act of 2010. The 1965 Act followed the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act that slowed the flow of African Caribbean immigration.

The UK was one of the undeniable centres of a definitive decade for the modern black existence. It was one of the main colonial powers from which African states became independent throughout the 1950s and 60s; a country where a number of pan African figures settled; the country that hosted three out of five pan-African congresses between 1919 and 1945, including the groundbreaking and pivotal 1945 congress in Manchester; the UK was a global power that attracted attention, however diminished it may have been following the second world war (if Britain still makes claims of being a leading power now, imagine its opinion of itself then which, to be fair, was probably still deserved in a pre-BRICS world); and it is a nation that can list a number of significant events during that decade alone, that show clearly the problem and the progress of the race issue.

Despite all this, I don't think you would ever know it was such a defining political and cultural decade. It remains off the mandatory schools curriculum (whilst it was a real achievement and may have been fit for its time, October's Black History Month has become an unfortunately haphazard way for schools to volunteer their efforts, with wildly varying degrees of success).

This decade at the centre of black, brown and British modern history deserves to be acknowledged in the same way as the simultaneous black civil rights movement in the US or the end of apartheid in South Africa are viewed globally, as significant moments in the black (and human!) struggle for freedom and equality and as defining moments in those nations histories. If it has been acknowledged, it has been with hushed reluctance at best. If it has been acknowledged, it has been through the under-funded efforts of elders and activists, against a backdrop of the Windrush Scandal (read more here).

A permanent (not 'opt-in') place in education, and hence the potential for entering our public consciousness regardless of socio-economic background, is the most meaningful way forward. Impermanent cultural outputs - we are all aware of sporadic or "on trend" newspaper articles, books, festivals, television programs etc - must do their drifting upon a bedrock of permanently educated understanding across our population. Black achievement in all its forms must be understood as an implicit and positive part of the British and English story.

As a cultural comparison, think for a moment about the musical cultural wave that took over the UK during that same period, with the influx of rock and roll and soul music from the United States. The role that North American blackness played in the development of youth and musical culture in the UK is undeniable and is acknowledged and celebrated (again sadly with some reluctance or negative spin from some quarters of society, such as the blatant racism of the infamous 'whites have become black' comments following the 2011 riots).

It comes as no surprise that a black contribution to singing and dancing is acknowledged and celebrated.

But, why has the political cultural side been almost entirely sidelined?

Does anyone think it is a coincidence that the equally vital Caribbean soundsystem culture, brought into the UK during the same period, is noticeably playing catchup on the acknowledgment and celebration stakes, having been similarly all but ignored by the mainstream?

It is noticeable whose black contribution to singing and dancing is acknowledged and celebrated.

Never too much of our own black British contribution. Here we see the paradigm our current movement of black musical stars continues to struggle with, albeit with some welcome success from a handful of standout artists.

It comes as no surprise that a black contribution to singing and dancing is acknowledged and celebrated.

But, why has the political cultural side been almost entirely sidelined?

Does anyone think it is a coincidence that the equally vital Caribbean soundsystem culture, brought into the UK during the same period, is noticeably playing catchup on the acknowledgment and celebration stakes, having been similarly all but ignored by the mainstream?

It is noticeable whose black contribution to singing and dancing is acknowledged and celebrated.

Never too much of our own black British contribution. Here we see the paradigm our current movement of black musical stars continues to struggle with, albeit with some welcome success from a handful of standout artists.

17th May. 1959.

When I think about Kelso Cochrane, killed on May 17th, 1959 in North Kensington, West London, I think about all of these things. Also, how so much can come down to the point of a knife and a brief moment that can end a life and begin something else entirely.

I doubt any of the things described would not have happened had he lived.

But, could it be said that so much more has happened because he died?

We are perhaps able to make a clearer go at seeing what his death contributed to.

And humans love things we can get hold of with our senses.

Discovering Kelso's death has lifted me and focused me, as much as it has drained me and angered me.

As an artist I am acutely aware that ones life can mean so much more in death. After all, we are people who actively construct an existence that can outlive us! Kelso's existence continues to be constructed.

I doubt any of the things described would not have happened had he lived.

But, could it be said that so much more has happened because he died?

We are perhaps able to make a clearer go at seeing what his death contributed to.

And humans love things we can get hold of with our senses.

Discovering Kelso's death has lifted me and focused me, as much as it has drained me and angered me.

As an artist I am acutely aware that ones life can mean so much more in death. After all, we are people who actively construct an existence that can outlive us! Kelso's existence continues to be constructed.

I have spent a lot of time thinking about Kelso and what his death means. I have spent time in various archives exploring the streets he lived in. I have spent a little precious time around people who are closer to him than I will ever be (I remain amazed at how I can now feel his physicality having met his daughter). I have spent nearly fifteen years on the corner where he fell. Local people and the local area have inspired me in countless ways.

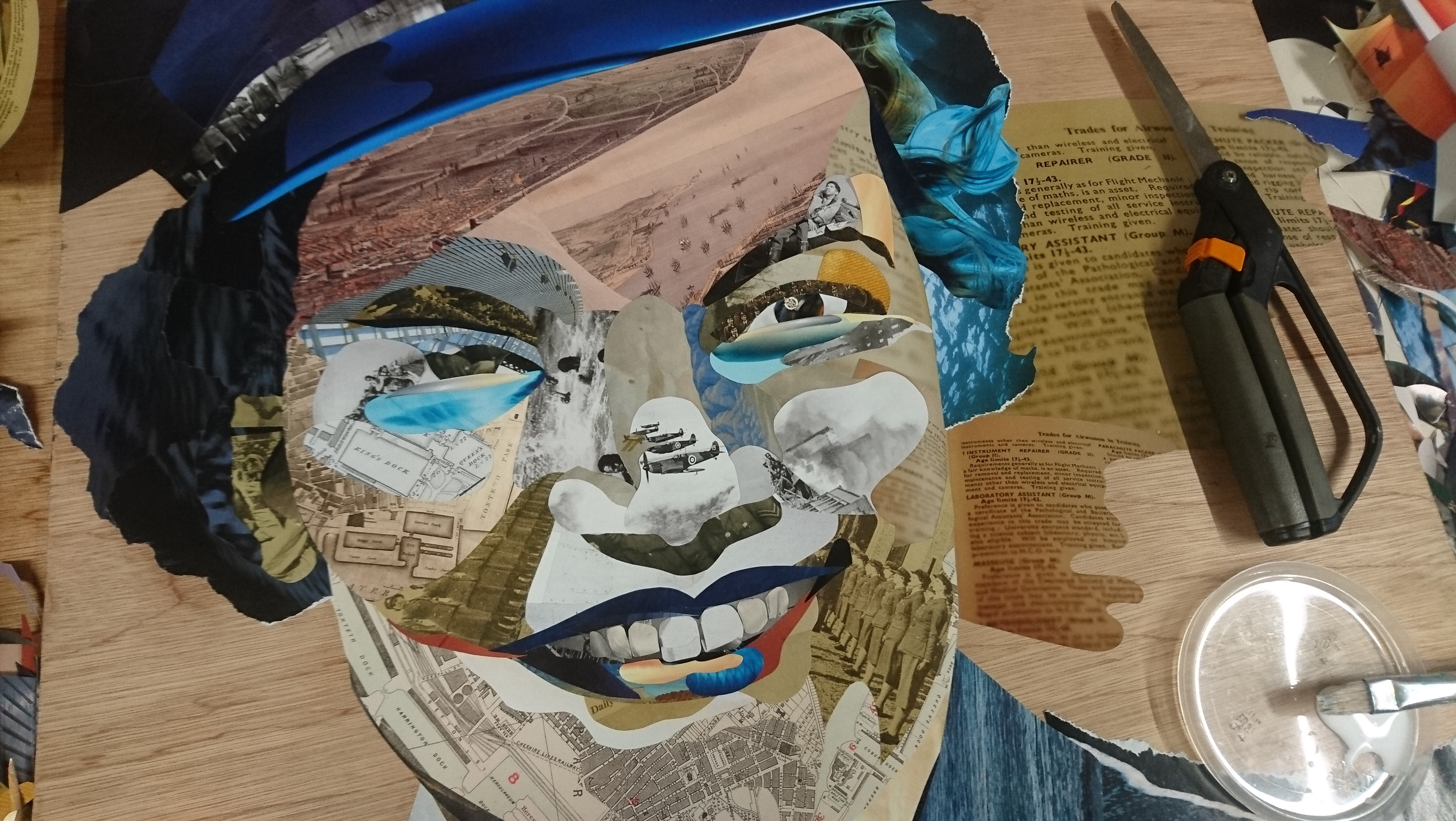

I will try to create a portrait of Kelso, with probably more pressure upon myself than with any artwork I have previously created.

I realise now, that in getting to know the impact of Kelso's death, I really know very little of his life.

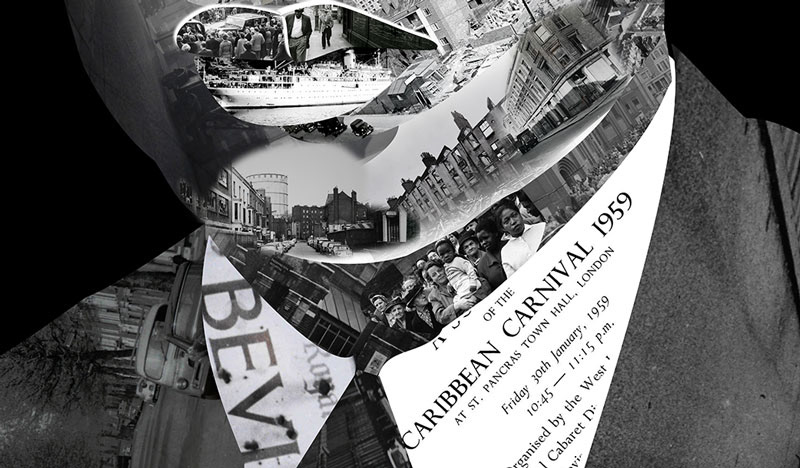

It is normal for a portrait artist to walk into a room with a subject they have barely, if ever, met and paint them. There is an amount of connection that you may make during the sitting. I replace that with hours of staring at photos of my subjects and thinking about them as I look through magazines and books. In this case, archive materials add an entirely new level to that. Working with the archives is something that has taken far more time and energy than I envisaged.

The resulting work from traditional portrait painting is intended to be a window into the person depicted.

However, in the case of my Samplism works (and perhaps even more so with the Pioneers portraits), they are consciously intended to be a window that opens out. I do not want to draw the viewer only inside of my subject. I want to draw the viewer outside of them. I want to give a suggestion of what a life was subjected to and conversely what a life (including death) may have affected.

I realise now, that in getting to know the impact of Kelso's death, I really know very little of his life.

It is normal for a portrait artist to walk into a room with a subject they have barely, if ever, met and paint them. There is an amount of connection that you may make during the sitting. I replace that with hours of staring at photos of my subjects and thinking about them as I look through magazines and books. In this case, archive materials add an entirely new level to that. Working with the archives is something that has taken far more time and energy than I envisaged.

The resulting work from traditional portrait painting is intended to be a window into the person depicted.

However, in the case of my Samplism works (and perhaps even more so with the Pioneers portraits), they are consciously intended to be a window that opens out. I do not want to draw the viewer only inside of my subject. I want to draw the viewer outside of them. I want to give a suggestion of what a life was subjected to and conversely what a life (including death) may have affected.

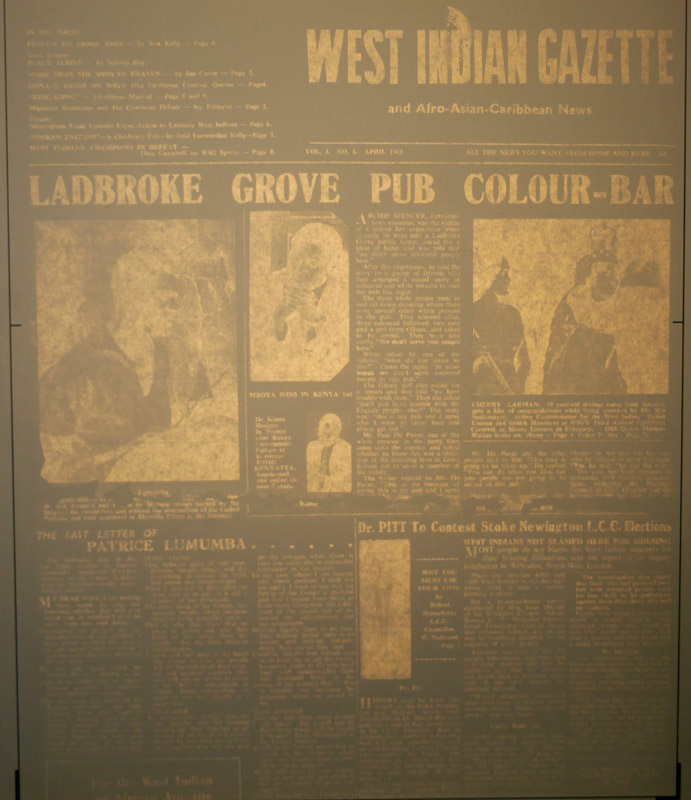

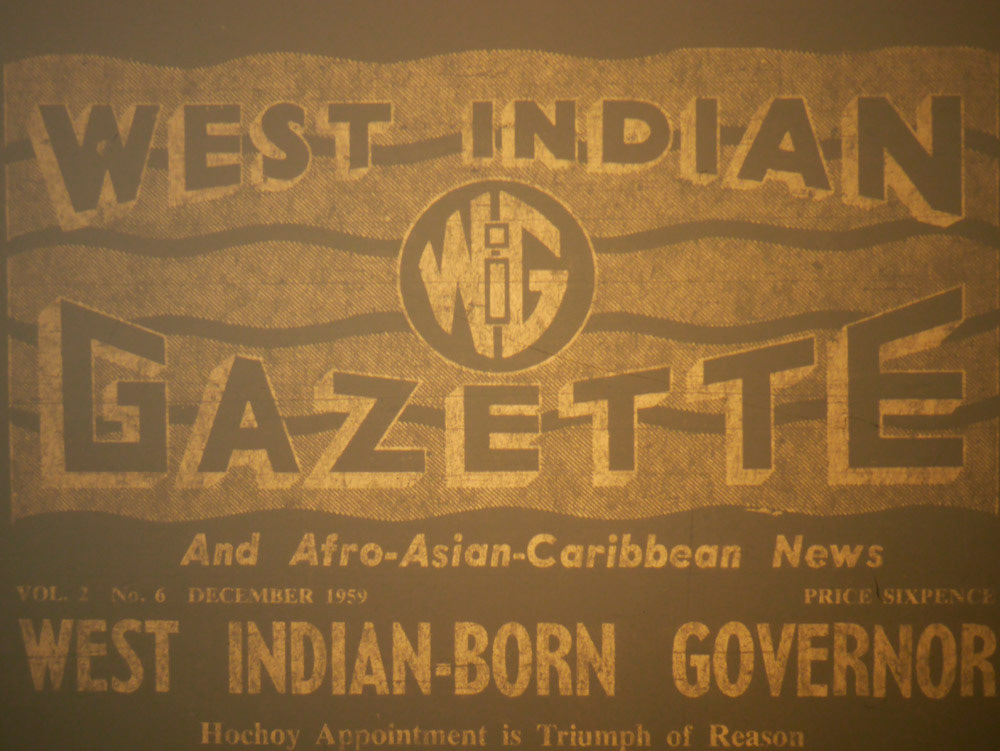

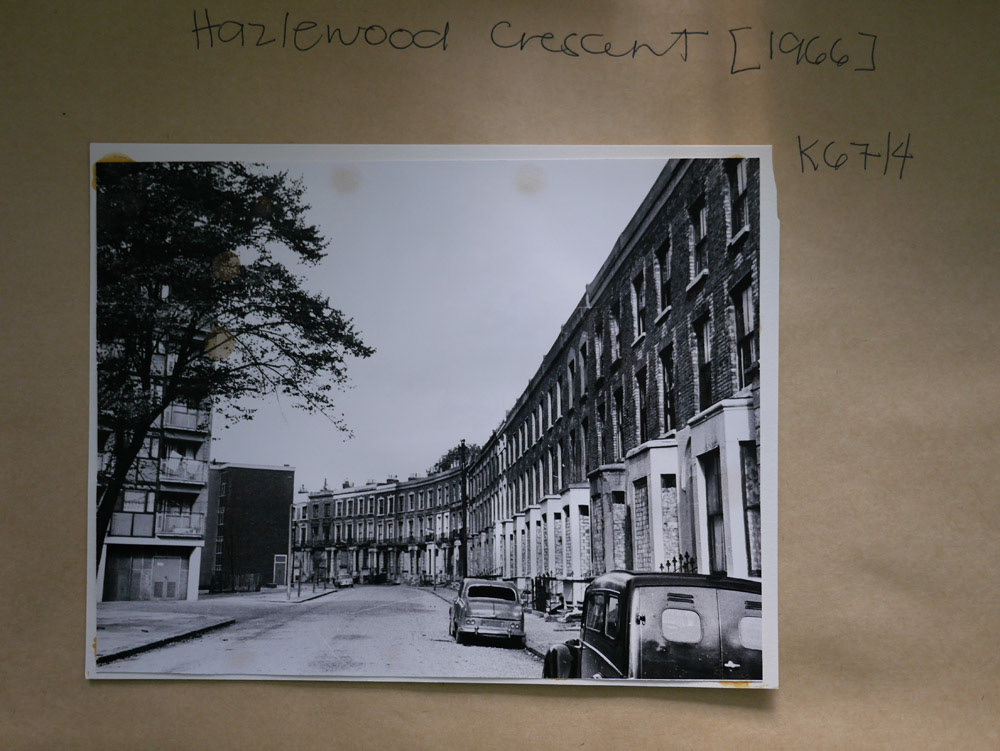

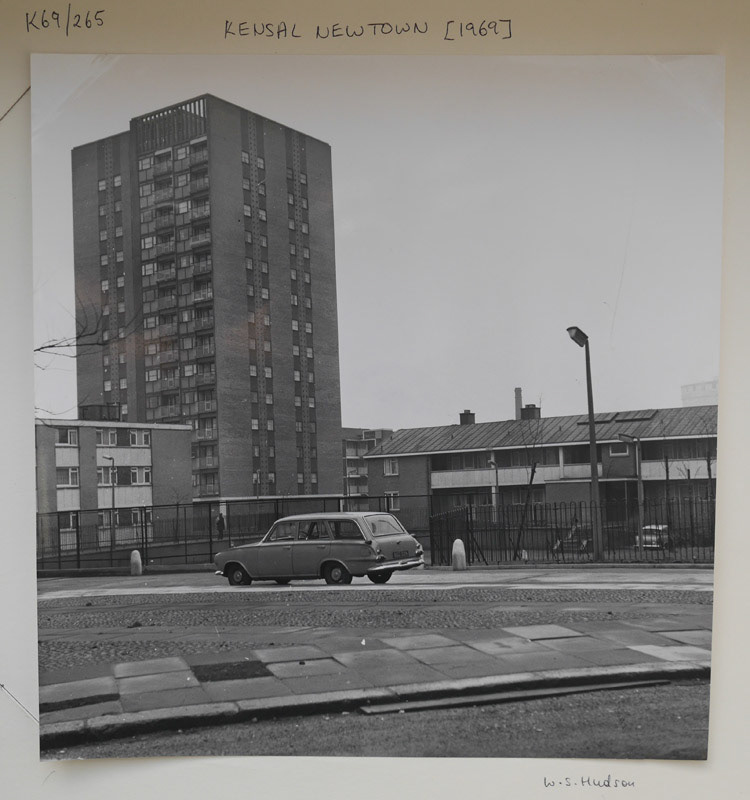

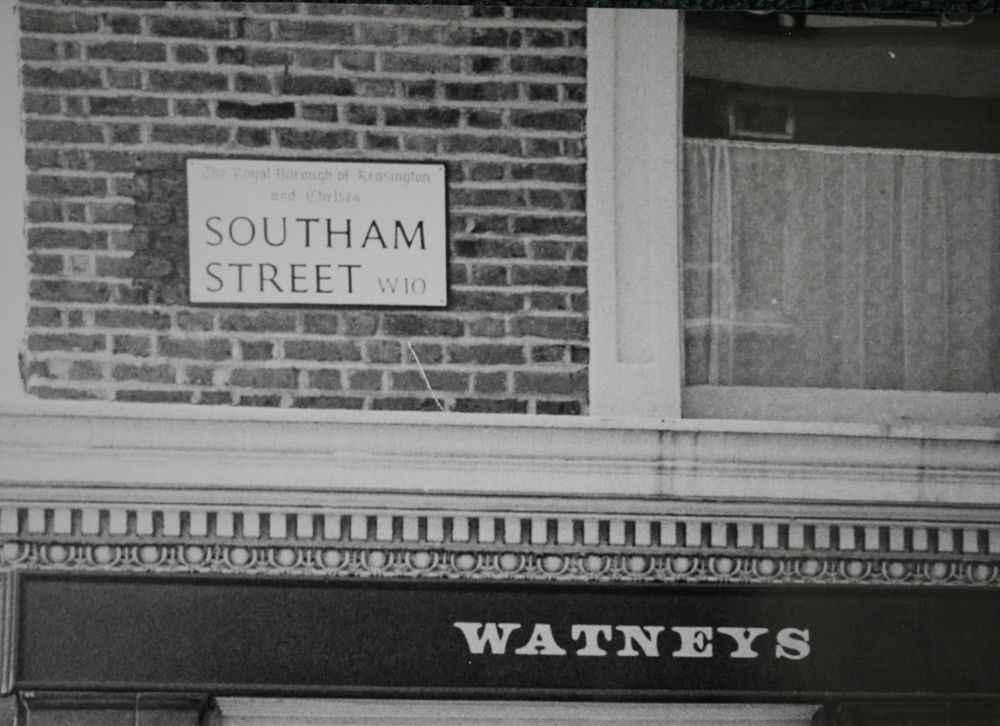

Here are a few of the images I will be using, including the streets of North Kensington, Paddington Hospital, the ship Kelso arrived on and the communications of the Colonial Office.

17th May 2020

The Final Artwork

The final digital Samplism portrait of Kelso was completed in March 2024. In May it was included in a commemorative booklet to mark 65 years since Kelso's death.

The final image does not contain images of the West Indian Gazette. It does reference the first Caribbean Carnival. But the main focus for this portrait is on the streets of North Kensington. Archive images of the streets in the 1950s and 60s show the very streets Kelso lived in - Bevington Road, Southam Street, Golborne Road; and the soon-to-arrive Trellick Tower and Holmefield House.

The SS Colombie, the ship Kelso most likely arrived to Britain on, can be found on his lips.

There is also strong reference to Oswald Mosley and the Fascists, whose presence in the local area may have appealed to those who killed Kelso. However, in the aftermath of Kelso's death that presence was rejected. They were washed out of our hair. They were cut from the streets and have never set foot back in the area. This placement of trauma in the hair echoes the portrait of Doreen Lawrence, where her hair contains the scene of her son's murder. Our hair is something powerful but mutable. It can contain, display and carry our pain. It can help us to move that pain out of our bodies. It can be an important part of our journey and our healing.

May 2024

Kelso 65 Blue Plaque

In May 2024, a blue plaque was unveiled in a beautiful small garden with an almond tree on Bevington Road, in the area where Kelso lived with his fiancee at the time of his passing.

A commemorative church service booklet includes pictures of his family in Antigua; the Samplism portrait of Kelso; maps and photographs of the area to show where Kelso lived, and the effect his death had on North Kensington.